I’m told the soul is what is left when a body dies. The first time I ate chitlins was at the same place my brother first ate chitlins, back when he worked at the discount paint store, and the boss had railed him out for fucking up the paint, because you had to match a three-quarter can of old white with a quarter can of old yellow to make cream, and had to make sure the raggedy old can lid clamped down good or you’d throw paint everywhere when you mixed it, and his co-worker felt bad for him, so he took him to lunch.

About how her daddy told her, you may be poor, but at least you ain’t Black. About the can of hardening fatback grease that would sit on the glassless windowsill and render unto them by rationed mounds the only trace of protein they often got. About drinking a whole glass of water right before you ate and a whole glass right after. About chewing every bite thirty times before you swallowed. My Grandmama talked about living off of livers and gizzards and poke salad, sassafras tea and chicory root. That you always wind up paying less than me, / But getting way more food?”Ĭhitlins, my Grandmama said, was something that, even in the depths of the Depression, they wouldn’t eat. In this ironic ballad of beauty, against a “faux-stone, faux-stucco” landscape of “screens and machines,” the question a friend poses is existential, urgent, and outright funny: “How is it.

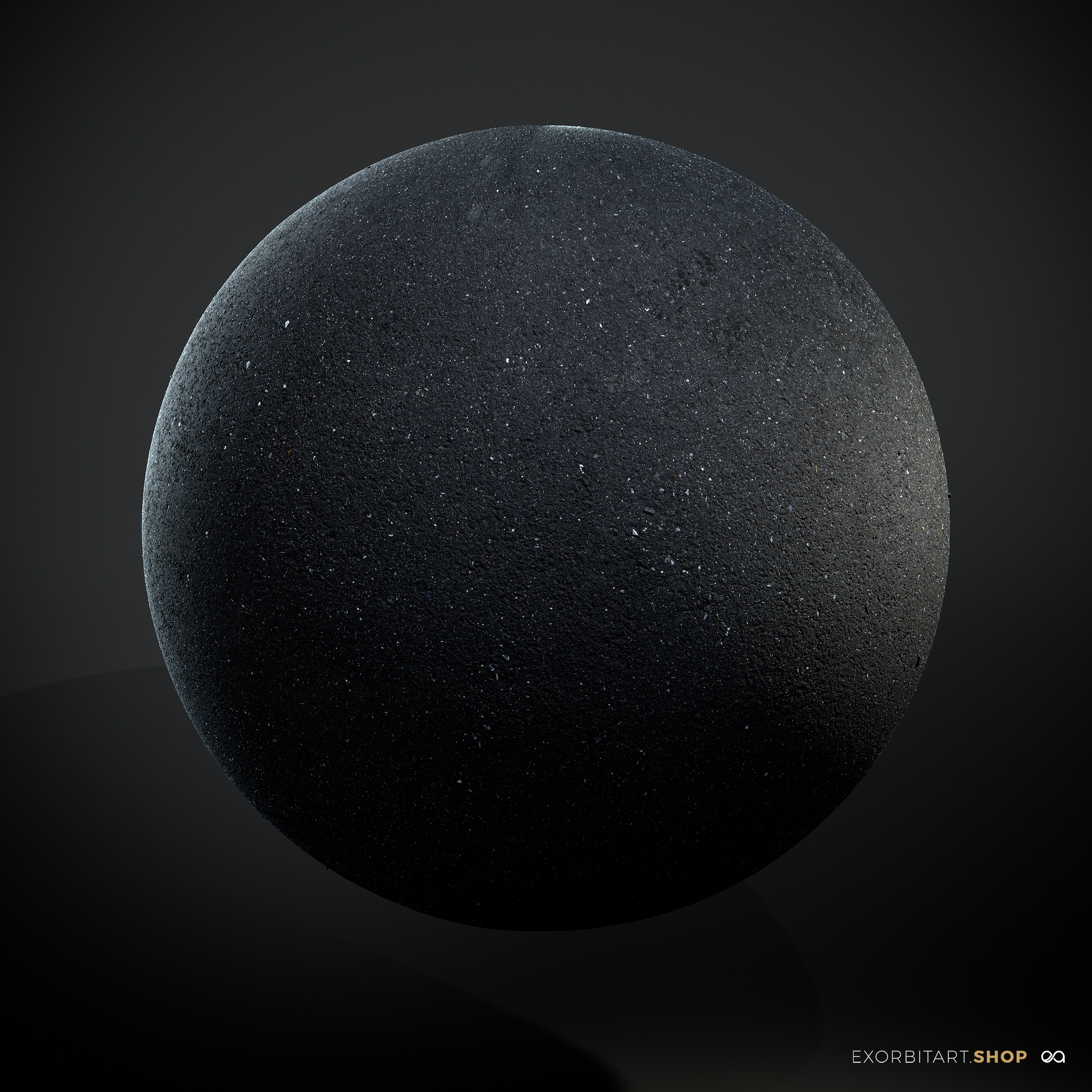

What Bains seeks, even as he critiques gluttony and greed, hunger and hypocrisy, is plenty. Paired here with photographs by the Atlanta-based artist Nydia Blas, Bains’s verse cascades across the page, reminiscent of mid-twentieth-century poetry’s composition by field-a practice lately left fallow. The labor that Bains foregrounds, although officially deemed “essential,” remains too often overlooked his poetry is a way of giving thanks when thanks is the least we might offer. This cycle of poems has the power of music, with an everyday elation that recalls the late Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s “ Coney Island of the Mind.” This is fitting, given Bains’s consideration of the carnival of cuisine that is the American South and which, indeed, composes our national diet-one that can careen wildly between homemade wonders, meat-and-three restaurants, and the familiar comforts and horrors of a “national fast-food entity.” He finds a feast of contradiction, too, in “the farmers’ market, / the locally grown section, / the organic superstore, / all worse.” Bains praises the working man’s lunch while commenting on both work and manhood, slyly referring to other lunch poems that don’t acknowledge where our daily bread comes from.Īs on his band’s 2014 album, “Dereconstructed,” Bains cuts a sweeping historical view with self-conscious reflection, taking pleasure in Southern traditions like barbecue and storytelling, and taking pains to describe being “stranded on the great shipwreck of Atlanta” while having “too much education / too little work / too much time / too little cash.” Though written before the COVID-19 pandemic, “Work Lunch” feels all the more crucial as farm, restaurant, grocery, delivery, and other food workers continue to toil amid threats to health, financial security, and wholeness. With his band, the Glory Fires, the Alabama native Lee Bains has long made music that sets out to catechize, celebrate, and complicate his Southern heritage-a project that extends to Bains’s freewheeling poetic sequence “Work Lunch,” which focusses not only on the food that sustains us but also on what, and who, makes such sustenance possible.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)